Recording Changes to the Repository

You have a bona fide Git repository and a checkout or working copy of the files for that project. You need to make some changes and commit snapshots of those changes into your repository each time the project reaches a state you want to record.

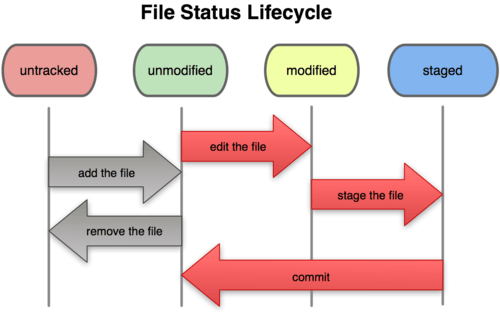

Remember that each file in your working directory can be in one of two states: tracked or untracked. Tracked files are files that were in the last snapshot; they can be unmodified, modified, or staged. Untracked files are everything else — any files in your working directory that were not in your last snapshot and are not in your staging area. When you first clone a repository, all of your files will be tracked and unmodified because you just checked them out and haven’t edited anything.

As you edit files, Git sees them as modified, because you’ve changed them since your last commit. You stage these modified files and then commit all your staged changes, and the cycle repeats. This lifecycle is illustrated in Figure 2-1.

Figure 2-1. The lifecycle of the status of your files.

Checking the Status of Your Files

The main tool you use to determine which files are in which state is the git status command. If you run this command directly after a clone, you should see something like this:

$ git status

On branch master

nothing to commit, working directory clean

This means you have a clean working directory — in other words, no tracked files are modified. Git also doesn’t see any untracked files, or they would be listed here. Finally, the command tells you which branch you’re on. For now, that is always master, which is the default; you won’t worry about it here. The next chapter will go over branches and references in detail.

Let’s say you add a new file to your project, a simple README file. If the file didn’t exist before, and you run git status, you see your untracked file like so:

$ vim README

$ git status

On branch master

Untracked files:

(use "git add <file>..." to include in what will be committed)

README

nothing added to commit but untracked files present (use "git add" to track)

You can see that your new README file is untracked, because it’s under the “Untracked files” heading in your status output. Untracked basically means that Git sees a file you didn’t have in the previous snapshot (commit); Git won’t start including it in your commit snapshots until you explicitly tell it to do so. It does this so you don’t accidentally begin including generated binary files or other files that you did not mean to include. You do want to start including README, so let’s start tracking the file.

Tracking New Files

In order to begin tracking a new file, you use the command git add. To begin tracking the README file, you can run this:

$ git add README

If you run your status command again, you can see that your README file is now tracked and staged:

$ git status

On branch master

Changes to be committed:

(use "git reset HEAD <file>..." to unstage)

new file: README

You can tell that it’s staged because it’s under the “Changes to be committed” heading. If you commit at this point, the version of the file at the time you ran git add is what will be in the historical snapshot. You may recall that when you ran git init earlier, you then ran git add (files) — that was to begin tracking files in your directory. The git add command takes a path name for either a file or a directory; if it’s a directory, the command adds all the files in that directory recursively.

Staging Modified Files

Let’s change a file that was already tracked. If you change a previously tracked file called benchmarks.rb and then run your status command again, you get something that looks like this:

$ git status

On branch master

Changes to be committed:

(use "git reset HEAD <file>..." to unstage)

new file: README

Changes not staged for commit:

(use "git add <file>..." to update what will be committed)

(use "git checkout -- <file>..." to discard changes in working directory)

modified: benchmarks.rb

The benchmarks.rb file appears under a section named “Changes not staged for commit” — which means that a file that is tracked has been modified in the working directory but not yet staged. To stage it, you run the git add command (it’s a multipurpose command — you use it to begin tracking new files, to stage files, and to do other things like marking merge-conflicted files as resolved). Let’s run git add now to stage the benchmarks.rb file, and then run git status again:

$ git add benchmarks.rb

$ git status

On branch master

Changes to be committed:

(use "git reset HEAD <file>..." to unstage)

new file: README

modified: benchmarks.rb

Both files are staged and will go into your next commit. At this point, suppose you remember one little change that you want to make in benchmarks.rb before you commit it. You open it again and make that change, and you’re ready to commit. However, let’s run git status one more time:

$ vim benchmarks.rb

$ git status

On branch master

Changes to be committed:

(use "git reset HEAD <file>..." to unstage)

new file: README

modified: benchmarks.rb

Changes not staged for commit:

(use "git add <file>..." to update what will be committed)

(use "git checkout -- <file>..." to discard changes in working directory)

modified: benchmarks.rb

What the heck? Now benchmarks.rb is listed as both staged and unstaged. How is that possible? It turns out that Git stages a file exactly as it is when you run the git add command. If you commit now, the version of benchmarks.rb as it was when you last ran the git add command is how it will go into the commit, not the version of the file as it looks in your working directory when you run git commit. If you modify a file after you run git add, you have to run git add again to stage the latest version of the file:

$ git add benchmarks.rb

$ git status

On branch master

Changes to be committed:

(use "git reset HEAD <file>..." to unstage)

new file: README

modified: benchmarks.rb

Ignoring Files

Often, you’ll have a class of files that you don’t want Git to automatically add or even show you as being untracked. These are generally automatically generated files such as log files or files produced by your build system. In such cases, you can create a file listing patterns to match them named .gitignore. Here is an example .gitignore file:

$ cat .gitignore

*.[oa]

*~

The first line tells Git to ignore any files ending in .o or .a — object and archive files that may be the product of building your code. The second line tells Git to ignore all files that end with a tilde (~), which is used by many text editors such as Emacs to mark temporary files. You may also include a log, tmp, or pid directory; automatically generated documentation; and so on. Setting up a .gitignore file before you get going is generally a good idea so you don’t accidentally commit files that you really don’t want in your Git repository.

The rules for the patterns you can put in the .gitignore file are as follows:

- Blank lines or lines starting with

#are ignored. - Standard glob patterns work.

- You can end patterns with a forward slash (

/) to specify a directory. - You can negate a pattern by starting it with an exclamation point (

!).

Glob patterns are like simplified regular expressions that shells use. An asterisk (*) matches zero or more characters; [abc] matches any character inside the brackets (in this case a, b, or c); a question mark (?) matches a single character; and brackets enclosing characters separated by a hyphen([0-9]) matches any character in the range (in this case 0 through 9) .

Here is another example .gitignore file:

# a comment - this is ignored

# no .a files

*.a

# but do track lib.a, even though you're ignoring .a files above

!lib.a

# only ignore the root TODO file, not subdir/TODO

/TODO

# ignore all files in the build/ directory

build/

# ignore doc/notes.txt, but not doc/server/arch.txt

doc/*.txt

# ignore all .txt files in the doc/ directory

doc/**/*.txt

A **/ pattern is available in Git since version 1.8.2.

Viewing Your Staged and Unstaged Changes

If the git status command is too vague for you — you want to know exactly what you changed, not just which files were changed — you can use the git diff command. We’ll cover git diff in more detail later; but you’ll probably use it most often to answer these two questions: What have you changed but not yet staged? And what have you staged that you are about to commit? Although git status answers those questions very generally, git diff shows you the exact lines added and removed — the patch, as it were.

Let’s say you edit and stage the README file again and then edit the benchmarks.rb file without staging it. If you run your status command, you once again see something like this:

$ git status

On branch master

Changes to be committed:

(use "git reset HEAD <file>..." to unstage)

new file: README

Changes not staged for commit:

(use "git add <file>..." to update what will be committed)

(use "git checkout -- <file>..." to discard changes in working directory)

modified: benchmarks.rb

To see what you’ve changed but not yet staged, type git diff with no other arguments:

$ git diff

diff --git a/benchmarks.rb b/benchmarks.rb

index 3cb747f..da65585 100644

--- a/benchmarks.rb

+++ b/benchmarks.rb

@@ -36,6 +36,10 @@ def main

@commit.parents[0].parents[0].parents[0]

end

+ run_code(x, 'commits 1') do

+ git.commits.size

+ end

+

run_code(x, 'commits 2') do

log = git.commits('master', 15)

log.size

That command compares what is in your working directory with what is in your staging area. The result tells you the changes you’ve made that you haven’t yet staged.

If you want to see what you’ve staged that will go into your next commit, you can use git diff --cached. (In Git versions 1.6.1 and later, you can also use git diff --staged, which may be easier to remember.) This command compares your staged changes to your last commit:

$ git diff --cached

diff --git a/README b/README

new file mode 100644

index 0000000..03902a1

--- /dev/null

+++ b/README2

@@ -0,0 +1,5 @@

+grit

+ by Tom Preston-Werner, Chris Wanstrath

+ http://github.com/mojombo/grit

+

+Grit is a Ruby library for extracting information from a Git repository

It’s important to note that git diff by itself doesn’t show all changes made since your last commit — only changes that are still unstaged. This can be confusing, because if you’ve staged all of your changes, git diff will give you no output.

For another example, if you stage the benchmarks.rb file and then edit it, you can use git diff to see the changes in the file that are staged and the changes that are unstaged:

$ git add benchmarks.rb

$ echo '# test line' >> benchmarks.rb

$ git status

On branch master

Changes to be committed:

(use "git reset HEAD <file>..." to unstage)

modified: benchmarks.rb

Changes not staged for commit:

(use "git add <file>..." to update what will be committed)

(use "git checkout -- <file>..." to discard changes in working directory)

modified: benchmarks.rb

Now you can use git diff to see what is still unstaged

$ git diff

diff --git a/benchmarks.rb b/benchmarks.rb

index e445e28..86b2f7c 100644

--- a/benchmarks.rb

+++ b/benchmarks.rb

@@ -127,3 +127,4 @@ end

main()

##pp Grit::GitRuby.cache_client.stats

+# test line

and git diff --cached to see what you’ve staged so far:

$ git diff --cached

diff --git a/benchmarks.rb b/benchmarks.rb

index 3cb747f..e445e28 100644

--- a/benchmarks.rb

+++ b/benchmarks.rb

@@ -36,6 +36,10 @@ def main

@commit.parents[0].parents[0].parents[0]

end

+ run_code(x, 'commits 1') do

+ git.commits.size

+ end

+

run_code(x, 'commits 2') do

log = git.commits('master', 15)

log.size

Committing Your Changes

Now that your staging area is set up the way you want it, you can commit your changes. Remember that anything that is still unstaged — any files you have created or modified that you haven’t run git add on since you edited them — won’t go into this commit. They will stay as modified files on your disk.

In this case, the last time you ran git status, you saw that everything was staged, so you’re ready to commit your changes. The simplest way to commit is to type git commit:

$ git commit

Doing so launches your editor of choice. (This is set by your shell’s $EDITOR environment variable — usually vim or emacs, although you can configure it with whatever you want using the git config --global core.editor command as you saw in Chapter 1).

The editor displays the following text (this example is a Vim screen):

# Please enter the commit message for your changes. Lines starting

# with '#' will be ignored, and an empty message aborts the commit.

# On branch master

# Changes to be committed:

# new file: README

# modified: benchmarks.rb

#

~

~

~

".git/COMMIT_EDITMSG" 10L, 283C

You can see that the default commit message contains the latest output of the git status command commented out and one empty line on top. You can remove these comments and type your commit message, or you can leave them there to help you remember what you’re committing. (For an even more explicit reminder of what you’ve modified, you can pass the -v option to git commit. Doing so also puts the diff of your change in the editor so you can see exactly what you did.) When you exit the editor, Git creates your commit with that commit message (with the comments and diff stripped out).

Alternatively, you can type your commit message inline with the commit command by specifying it after a -m flag, like this:

$ git commit -m "Story 182: Fix benchmarks for speed"

[master 463dc4f] Fix benchmarks for speed

2 files changed, 3 insertions(+)

create mode 100644 README

Now you’ve created your first commit! You can see that the commit has given you some output about itself: which branch you committed to (master), what SHA-1 checksum the commit has (463dc4f), how many files were changed, and statistics about lines added and removed in the commit.

Remember that the commit records the snapshot you set up in your staging area. Anything you didn’t stage is still sitting there modified; you can do another commit to add it to your history. Every time you perform a commit, you’re recording a snapshot of your project that you can revert to or compare to later.

Skipping the Staging Area

Although it can be amazingly useful for crafting commits exactly how you want them, the staging area is sometimes a bit more complex than you need in your workflow. If you want to skip the staging area, Git provides a simple shortcut. Providing the -a option to the git commit command makes Git automatically stage every file that is already tracked before doing the commit, letting you skip the git add part:

$ git status

On branch master

Changes not staged for commit:

(use "git add <file>..." to update what will be committed)

(use "git checkout -- <file>..." to discard changes in working directory)

modified: benchmarks.rb

no changes added to commit (use "git add" and/or "git commit -a")

$ git commit -a -m 'added new benchmarks'

[master 83e38c7] added new benchmarks

1 files changed, 5 insertions(+)

Notice how you don’t have to run git add on the benchmarks.rb file in this case before you commit.

Removing Files

To remove a file from Git, you have to remove it from your tracked files (more accurately, remove it from your staging area) and then commit. The git rm command does that and also removes the file from your working directory so you don’t see it as an untracked file next time around.

If you simply remove the file from your working directory, it shows up under the “Changes not staged for commit” (that is, unstaged) area of your git status output:

$ rm grit.gemspec

$ git status

On branch master

Changes not staged for commit:

(use "git add/rm <file>..." to update what will be committed)

(use "git checkout -- <file>..." to discard changes in working directory)

deleted: grit.gemspec

no changes added to commit (use "git add" and/or "git commit -a")

Then, if you run git rm, it stages the file’s removal:

$ git rm grit.gemspec

rm 'grit.gemspec'

$ git status

On branch master

Changes to be committed:

(use "git reset HEAD <file>..." to unstage)

deleted: grit.gemspec

The next time you commit, the file will be gone and no longer tracked. If you modified the file and added it to the index already, you must force the removal with the -f option. This is a safety feature to prevent accidental removal of data that hasn’t yet been recorded in a snapshot and that can’t be recovered from Git.

Another useful thing you may want to do is to keep the file in your working tree but remove it from your staging area. In other words, you may want to keep the file on your hard drive but not have Git track it anymore. This is particularly useful if you forgot to add something to your .gitignore file and accidentally staged it, like a large log file or a bunch of .a compiled files. To do this, use the --cached option:

$ git rm --cached readme.txt

You can pass files, directories, and file-glob patterns to the git rm command. That means you can do things such as

$ git rm log/\*.log

Note the backslash (\) in front of the *. This is necessary because Git does its own filename expansion in addition to your shell’s filename expansion. On Windows with the system console, the backslash must be omitted. This command removes all files that have the .log extension in the log/ directory. Or, you can do something like this:

$ git rm \*~

This command removes all files that end with ~.

Moving Files

Unlike many other VCS systems, Git doesn’t explicitly track file movement. If you rename a file in Git, no metadata is stored in Git that tells it you renamed the file. However, Git is pretty smart about figuring that out after the fact — we’ll deal with detecting file movement a bit later.

Thus it’s a bit confusing that Git has a mv command. If you want to rename a file in Git, you can run something like

$ git mv file_from file_to

and it works fine. In fact, if you run something like this and look at the status, you’ll see that Git considers it a renamed file:

$ git mv README.txt README

$ git status

On branch master

Changes to be committed:

(use "git reset HEAD <file>..." to unstage)

renamed: README.txt -> README

However, this is equivalent to running something like this:

$ mv README.txt README

$ git rm README.txt

$ git add README

Git figures out that it’s a rename implicitly, so it doesn’t matter if you rename a file that way or with the mv command. The only real difference is that mv is one command instead of three — it’s a convenience function. More important, you can use any tool you like to rename a file, and address the add/rm later, before you commit.