Basic Branching and Merging

Let’s go through a simple example of branching and merging with a workflow that you might use in the real world. You’ll follow these steps:

- Do work on a web site.

- Create a branch for a new story you’re working on.

- Do some work in that branch.

At this stage, you’ll receive a call that another issue is critical and you need a hotfix. You’ll do the following:

- Switch back to your production branch.

- Create a branch to add the hotfix.

- After it’s tested, merge the hotfix branch, and push to production.

- Switch back to your original story and continue working.

Basic Branching

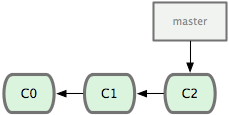

First, let’s say you’re working on your project and have a couple of commits already (see Figure 3-10).

Figure 3-10. A short and simple commit history.

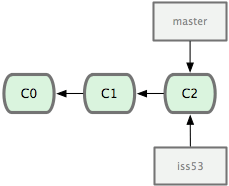

You’ve decided that you’re going to work on issue #53 in whatever issue-tracking system your company uses. To be clear, Git isn’t tied into any particular issue-tracking system; but because issue #53 is a focused topic that you want to work on, you’ll create a new branch in which to work. To create a branch and switch to it at the same time, you can run the git checkout command with the -b switch:

$ git checkout -b iss53

Switched to a new branch 'iss53'

This is shorthand for:

$ git branch iss53

$ git checkout iss53

Figure 3-11 illustrates the result.

Figure 3-11. Creating a new branch pointer.

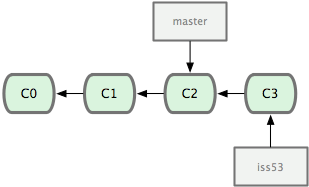

You work on your web site and do some commits. Doing so moves the iss53 branch forward, because you have it checked out (that is, your HEAD is pointing to it; see Figure 3-12):

$ vim index.html

$ git commit -a -m 'added a new footer [issue 53]'

Figure 3-12. The iss53 branch has moved forward with your work.

Now you get the call that there is an issue with the web site, and you need to fix it immediately. With Git, you don’t have to deploy your fix along with the iss53 changes you’ve made, and you don’t have to put a lot of effort into reverting those changes before you can work on applying your fix to what is in production. All you have to do is switch back to your master branch.

However, before you do that, note that if your working directory or staging area has uncommitted changes that conflict with the branch you’re checking out, Git won’t let you switch branches. It’s best to have a clean working state when you switch branches. There are ways to get around this (namely, stashing and commit amending) that we’ll cover later. For now, you’ve committed all your changes, so you can switch back to your master branch:

$ git checkout master

Switched to branch 'master'

At this point, your project working directory is exactly the way it was before you started working on issue #53, and you can concentrate on your hotfix. This is an important point to remember: Git resets your working directory to look like the snapshot of the commit that the branch you check out points to. It adds, removes, and modifies files automatically to make sure your working copy is what the branch looked like on your last commit to it.

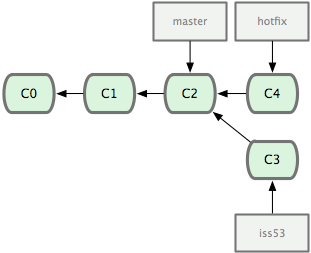

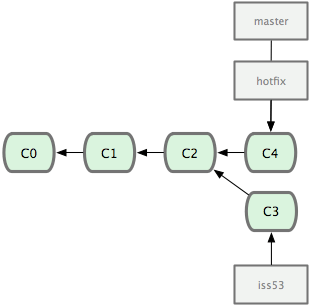

Next, you have a hotfix to make. Let’s create a hotfix branch on which to work until it’s completed (see Figure 3-13):

$ git checkout -b hotfix

Switched to a new branch 'hotfix'

$ vim index.html

$ git commit -a -m 'fixed the broken email address'

[hotfix 3a0874c] fixed the broken email address

1 files changed, 1 deletion(-)

Figure 3-13. hotfix branch based back at your master branch point.

You can run your tests, make sure the hotfix is what you want, and merge it back into your master branch to deploy to production. You do this with the git merge command:

$ git checkout master

$ git merge hotfix

Updating f42c576..3a0874c

Fast-forward

README | 1 -

1 file changed, 1 deletion(-)

You’ll notice the phrase "Fast-forward" in that merge. Because the commit pointed to by the branch you merged in was directly upstream of the commit you’re on, Git moves the pointer forward. To phrase that another way, when you try to merge one commit with a commit that can be reached by following the first commit’s history, Git simplifies things by moving the pointer forward because there is no divergent work to merge together — this is called a "fast forward".

Your change is now in the snapshot of the commit pointed to by the master branch, and you can deploy your change (see Figure 3-14).

Figure 3-14. Your master branch points to the same place as your hotfix branch after the merge.

After your super-important fix is deployed, you’re ready to switch back to the work you were doing before you were interrupted. However, first you’ll delete the hotfix branch, because you no longer need it — the master branch points at the same place. You can delete it with the -d option to git branch:

$ git branch -d hotfix

Deleted branch hotfix (was 3a0874c).

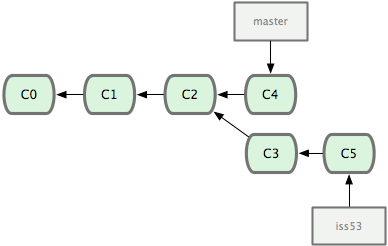

Now you can switch back to your work-in-progress branch on issue #53 and continue working on it (see Figure 3-15):

$ git checkout iss53

Switched to branch 'iss53'

$ vim index.html

$ git commit -a -m 'finished the new footer [issue 53]'

[iss53 ad82d7a] finished the new footer [issue 53]

1 file changed, 1 insertion(+)

Figure 3-15. Your iss53 branch can move forward independently.

It’s worth noting here that the work you did in your hotfix branch is not contained in the files in your iss53 branch. If you need to pull it in, you can merge your master branch into your iss53 branch by running git merge master, or you can wait to integrate those changes until you decide to pull the iss53 branch back into master later.

Basic Merging

Suppose you’ve decided that your issue #53 work is complete and ready to be merged into your master branch. In order to do that, you’ll merge in your iss53 branch, much like you merged in your hotfix branch earlier. All you have to do is check out the branch you wish to merge into and then run the git merge command:

$ git checkout master

$ git merge iss53

Auto-merging README

Merge made by the 'recursive' strategy.

README | 1 +

1 file changed, 1 insertion(+)

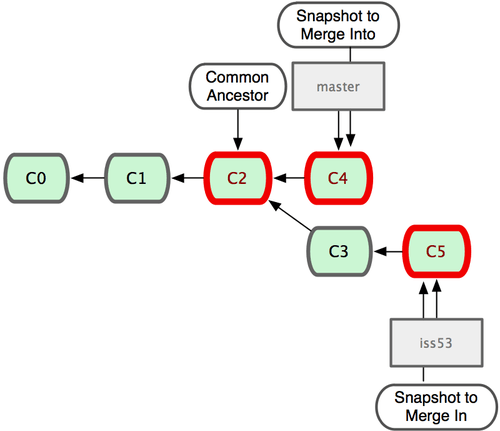

This looks a bit different than the hotfix merge you did earlier. In this case, your development history has diverged from some older point. Because the commit on the branch you’re on isn’t a direct ancestor of the branch you’re merging in, Git has to do some work. In this case, Git does a simple three-way merge, using the two snapshots pointed to by the branch tips and the common ancestor of the two. Figure 3-16 highlights the three snapshots that Git uses to do its merge in this case.

Figure 3-16. Git automatically identifies the best common-ancestor merge base for branch merging.

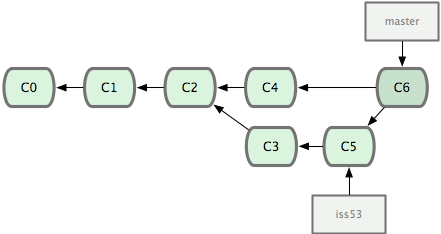

Instead of just moving the branch pointer forward, Git creates a new snapshot that results from this three-way merge and automatically creates a new commit that points to it (see Figure 3-17). This is referred to as a merge commit and is special in that it has more than one parent.

It’s worth pointing out that Git determines the best common ancestor to use for its merge base; this is different than CVS or Subversion (before version 1.5), where the developer doing the merge has to figure out the best merge base for themselves. This makes merging a heck of a lot easier in Git than in these other systems.

Figure 3-17. Git automatically creates a new commit object that contains the merged work.

Now that your work is merged in, you have no further need for the iss53 branch. You can delete it and then manually close the ticket in your ticket-tracking system:

$ git branch -d iss53

Basic Merge Conflicts

Occasionally, this process doesn’t go smoothly. If you changed the same part of the same file differently in the two branches you’re merging together, Git won’t be able to merge them cleanly. If your fix for issue #53 modified the same part of a file as the hotfix, you’ll get a merge conflict that looks something like this:

$ git merge iss53

Auto-merging index.html

CONFLICT (content): Merge conflict in index.html

Automatic merge failed; fix conflicts and then commit the result.

Git hasn’t automatically created a new merge commit. It has paused the process while you resolve the conflict. If you want to see which files are unmerged at any point after a merge conflict, you can run git status:

$ git status

On branch master

You have unmerged paths.

(fix conflicts and run "git commit")

Unmerged paths:

(use "git add <file>..." to mark resolution)

both modified: index.html

no changes added to commit (use "git add" and/or "git commit -a")

Anything that has merge conflicts and hasn’t been resolved is listed as unmerged. Git adds standard conflict-resolution markers to the files that have conflicts, so you can open them manually and resolve those conflicts. Your file contains a section that looks something like this:

<<<<<<< HEAD

<div id="footer">contact : [email protected]</div>

=======

<div id="footer">

please contact us at [email protected]

</div>

>>>>>>> iss53

This means the version in HEAD (your master branch, because that was what you had checked out when you ran your merge command) is the top part of that block (everything above the =======), while the version in your iss53 branch looks like everything in the bottom part. In order to resolve the conflict, you have to either choose one side or the other or merge the contents yourself. For instance, you might resolve this conflict by replacing the entire block with this:

<div id="footer">

please contact us at [email protected]

</div>

This resolution has a little of each section, and I’ve fully removed the <<<<<<<, =======, and >>>>>>> lines. After you’ve resolved each of these sections in each conflicted file, run git add on each file to mark it as resolved. Staging the file marks it as resolved in Git.

If you want to use a graphical tool to resolve these issues, you can run git mergetool, which fires up an appropriate visual merge tool and walks you through the conflicts:

$ git mergetool

This message is displayed because 'merge.tool' is not configured.

See 'git mergetool --tool-help' or 'git help config' for more details.

'git mergetool' will now attempt to use one of the following tools:

opendiff kdiff3 tkdiff xxdiff meld tortoisemerge gvimdiff diffuse diffmerge ecmerge p4merge araxis bc3 codecompare vimdiff emerge

Merging:

index.html

Normal merge conflict for 'index.html':

{local}: modified file

{remote}: modified file

Hit return to start merge resolution tool (opendiff):

If you want to use a merge tool other than the default (Git chose opendiff for me in this case because I ran the command on a Mac), you can see all the supported tools listed at the top after “... one of the following tools:”. Type the name of the tool you’d rather use. In Chapter 7, we’ll discuss how you can change this default value for your environment.

After you exit the merge tool, Git asks you if the merge was successful. If you tell the script that it was, it stages the file to mark it as resolved for you.

You can run git status again to verify that all conflicts have been resolved:

$ git status

On branch master

Changes to be committed:

(use "git reset HEAD <file>..." to unstage)

modified: index.html

If you’re happy with that, and you verify that everything that had conflicts has been staged, you can type git commit to finalize the merge commit. The commit message by default looks something like this:

Merge branch 'iss53'

Conflicts:

index.html

#

# It looks like you may be committing a merge.

# If this is not correct, please remove the file

# .git/MERGE_HEAD

# and try again.

#

You can modify that message with details about how you resolved the merge if you think it would be helpful to others looking at this merge in the future — why you did what you did, if it’s not obvious.